Panic attacks are more than fleeting moments of fear—they’re intense, often debilitating experiences that can reshape how we live, think, and connect. This in-depth guide explores the neurobiology behind panic attacks, from amygdala hyperactivity to the “false suffocation alarm” theory, and unpacks the psychological and environmental factors that contribute to their onset. Whether you’re a mental health advocate, a clinician, or someone seeking clarity for personal healing, this post offers evidence-based insights into diagnosis, treatment options like CBT and medication, and practical self-help strategies. Empower yourself with knowledge and discover how recovery is not only possible—but probable.

Introduction

Panic attacks represent one of the most distressing and disabling experiences in mental health, characterized by sudden, overwhelming episodes of intense fear and physical symptoms that can leave sufferers feeling as though they are dying or losing control. These episodes, which peak within minutes and can occur without apparent triggers, affect millions of people worldwide and significantly impact quality of life, relationships, and daily functioning.

While panic attacks can be isolated incidents, they often develop into panic disorder when accompanied by persistent worry about future attacks and behavioral changes designed to avoid potential triggers. Understanding the complex neurobiological mechanisms underlying panic attacks, their various causes, and the evidence-based treatments available is crucial for both healthcare providers and individuals seeking relief from this debilitating condition.

The Neurobiology of Panic: Understanding the Brain’s Fear Response

The Central Fear Network

The human brain’s response to perceived threats involves a sophisticated network of interconnected structures that, when functioning normally, help us respond appropriately to danger. However, in panic attacks, this system becomes hyperactive and dysregulated, triggering intense fear responses in the absence of actual threats.

The amygdala, an almond-shaped structure deep within the brain, serves as the central hub of fear processing. Research has consistently shown that individuals with panic disorder exhibit hyperactive and smaller amygdalae compared to healthy controls. The amygdala’s role in panic is so significant that electrical or chemical stimulation of its central nucleus can produce symptoms virtually identical to those experienced during panic attacks.

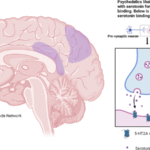

Connected to the amygdala is a broader fear network that includes the hippocampus (involved in memory and context processing), the hypothalamus (regulating hormonal responses), the thalamus (relay station for sensory information), and various brainstem structures including the locus ceruleus and periaqueductal gray. This network operates through complex interactions between multiple neurotransmitter systems, including serotonin, norepinephrine, and GABA.

The Role of Brain Chemistry

Neurotransmitter imbalances play a crucial role in panic disorder pathophysiology. Research has identified several key chemical systems involved:

GABA System Dysfunction: Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) serves as the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, normally providing a “braking” effect on neural excitation. In panic disorder, studies have found reduced GABA receptor binding in the amygdala, leading to decreased inhibitory control over fear responses. This reduction in GABAergic function allows fear circuits to become hyperactive and difficult to regulate.

Serotonin Dysregulation: The serotonin system normally provides a restraining influence on panic-generating brain regions. In panic disorder, this restraint system appears compromised, allowing for excessive neural activity in fear circuits. This dysfunction explains why SSRI medications, which enhance serotonin function, are effective treatments for panic disorder.

Norepinephrine Hyperactivity: The locus ceruleus, a brainstem nucleus that produces norepinephrine, shows heightened activity in panic disorder. This hyperactivity contributes to the physical symptoms of panic attacks, including rapid heart rate, sweating, and trembling.

The False Suffocation Alarm Theory

One of the most compelling neurobiological explanations for panic attacks is the “false suffocation alarm” theory. This theory suggests that individuals with panic disorder have hypersensitive chemoreceptors in the brainstem that monitor carbon dioxide levels and pH balance in the blood. When these receptors are triggered inappropriately, they create a false sense of suffocation, leading to the characteristic breathing difficulties and sense of impending doom experienced during panic attacks.

This theory is supported by the fact that panic attacks can be induced in susceptible individuals through lactate infusion or carbon dioxide inhalation, both of which affect blood chemistry in ways similar to suffocation. The amygdala contains acid-sensing ion channels that may be triggered by these chemical changes, creating a cascade of panic symptoms.

Understanding Panic Attack Symptoms and Diagnostic Criteria

Defining a Panic Attack

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a panic attack is characterized by four or more of the following 13 symptoms developing abruptly and reaching peak intensity within 10 minutes:

Physical Symptoms:

- Palpitations, pounding heart, or accelerated heart rate

- Sweating

- Trembling or shaking

- Sensations of shortness of breath or smothering

- Feeling of choking

- Chest pain or discomfort

- Nausea or abdominal distress

- Feeling dizzy, unsteady, lightheaded, or faint

- Chills or hot flashes

- Numbness or tingling sensations (paresthesias)

Psychological Symptoms:

- Feelings of unreality (derealization) or being detached from oneself (depersonalization)

- Fear of losing control or “going crazy”

- Fear of dying

The presence of fewer than four symptoms may be considered a “limited-symptom panic attack,” which can still be distressing but doesn’t meet the full diagnostic criteria.

Panic Disorder vs. Isolated Panic Attacks

While many people may experience occasional panic attacks, panic disorder represents a more serious condition requiring specific diagnostic criteria. To be diagnosed with panic disorder, an individual must experience:

- Recurrent unexpected panic attacks

- At least one month of persistent worry about having additional attacks or their consequences

- Significant behavioral changes related to the attacks (such as avoiding situations where attacks might occur)

- Attacks are not attributable to substance use, medical conditions, or other mental health disorders

The DSM-5 now recognizes two types of panic attacks: expected attacks (those with identifiable triggers) and unexpected attacks (those that appear to occur “out of the blue”). This distinction is important because unexpected attacks are more characteristic of panic disorder.

Risk Factors and Causes of Panic Attacks

Genetic Factors

Research consistently demonstrates that panic disorder has a strong genetic component, with family, twin, and adoption studies all supporting hereditary influences. Family studies show that first-degree relatives of individuals with panic disorder have a 5-17 fold increased risk of developing the condition compared to the general population.

Twin studies reveal particularly compelling evidence, with monozygotic twins showing significantly higher concordance rates than dizygotic twins. The heritability of panic disorder is estimated to be approximately 40-50%, indicating substantial genetic influence while still leaving room for environmental factors.

Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified several candidate genes associated with panic disorder, including:

- NPY (neuropeptide Y) – involved in stress response regulation

- ADORA2A (adenosine A2A receptor) – affects anxiety and arousal

- COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase) – metabolizes stress-related neurotransmitters

- MAOA (monoamine oxidase A) – breaks down mood-regulating neurotransmitters

Interestingly, many genetic associations show gender-specific patterns, which may help explain why panic disorder affects women at higher rates than men.

Environmental and Psychological Factors

While genetics provide vulnerability, environmental factors often serve as triggers for panic disorder development. Common environmental risk factors include:

Childhood Trauma and Adversity: Early life stress, abuse, or neglect can sensitize fear circuits and increase panic disorder risk later in life.

Major Life Stressors: Significant life events such as loss of a loved one, divorce, job loss, or major illness can precipitate panic attacks in vulnerable individuals.

Substance Use: Caffeine, alcohol, cannabis, and other substances can trigger panic attacks, particularly during withdrawal periods.

Medical Conditions: Certain medical conditions can either cause panic-like symptoms or increase vulnerability to panic attacks:

- Hyperthyroidism

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Respiratory conditions (asthma, COPD)

- Vestibular disorders

- Hypoglycemia

Psychological Vulnerability Factors

Several psychological factors increase panic attack susceptibility:

Anxiety Sensitivity: This refers to the fear of anxiety-related sensations, such as rapid heartbeat or dizziness. Individuals high in anxiety sensitivity are more likely to interpret normal bodily sensations as dangerous, potentially triggering panic attacks.

Catastrophic Thinking: The tendency to interpret minor physical sensations or situations in catastrophic terms can fuel the fear-panic cycle.

Interoceptive Awareness: Heightened awareness of internal bodily sensations can lead to misinterpretation of normal physiological changes as signs of danger.

Prevalence and Demographics

Population Statistics

Panic disorder affects a significant portion of the global population, with lifetime prevalence rates ranging from 2-6% of adults. In the United States:

- Annual prevalence: Approximately 2.7% of adults experience panic disorder each year

- Lifetime prevalence: An estimated 4.7% of adults will experience panic disorder at some point in their lives

- Adolescent prevalence: About 2.3% of adolescents aged 13-18 experience panic disorder

Gender Differences

Panic disorder shows a strong gender bias, affecting women at rates 2-3 times higher than men:

- Female prevalence: 3.8% annually, 2.6% among adolescents

- Male prevalence: 1.6% annually, 2.0% among adolescents

This gender difference may be related to hormonal factors, genetic variations, and different stress response patterns between men and women.

Age of Onset

Panic disorder typically emerges in young adulthood, with the mean age of onset between 20-24 years. However, the disorder can develop across the lifespan:

- Adolescence (13-18): 2.3% prevalence, with peak onset between ages 15-19

- Young adults (18-29): 2.8% prevalence

- Middle age (30-44): 3.7% prevalence

- Older adults (60+): 0.8% prevalence

The lower prevalence in older adults may reflect cohort effects, successful treatment, or natural remission over time.

Comorbidity and Complications

Panic disorder rarely occurs in isolation. Comorbid conditions are extremely common and include:

Agoraphobia: Fear of places or situations where escape might be difficult affects approximately 42.3% of individuals with panic disorder.

Depression: Co-occurs in about 30.9% of panic disorder cases, significantly complicating treatment and prognosis.

Substance Use Disorders: Approximately 30% of individuals with panic disorder misuse alcohol, while 17% misuse drugs such as cocaine and marijuana.

Medical Conditions: Panic disorder is associated with increased rates of:

- Coronary heart disease (47% increased risk)

- Respiratory conditions (25% of COPD patients, 20% of asthma patients have panic disorder)

- Gastrointestinal disorders

Suicide Risk: Perhaps most concerning, 42% of people with panic disorder have a history of suicide attempts, with 64.3% of attempts occurring after disorder onset.

Evidence-Based Treatment Approaches

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy represents the gold standard psychological treatment for panic disorder, with extensive research demonstrating its effectiveness. CBT for panic disorder typically involves 12-15 sessions conducted over 3-6 months and addresses both the cognitive and behavioral components of panic.

Cognitive Components

The cognitive aspect of CBT helps patients understand how their thoughts and interpretations of physical sensations contribute to panic attacks. Key cognitive interventions include:

Psychoeducation: Patients learn about the neurophysiology of panic, understanding that panic attacks, while frightening, are not dangerous and will naturally subside.

Cognitive Restructuring: This involves identifying and challenging catastrophic thoughts that fuel panic attacks. For example, a patient who interprets heart palpitations as a sign of heart attack learns to recognize this as anxiety sensitivity rather than medical emergency.

Thought Monitoring: Patients learn to identify automatic negative thoughts that precede or accompany panic attacks, developing awareness of the thought-panic cycle.

Behavioral Components

The behavioral aspects of CBT involve exposure-based interventions designed to reduce avoidance and build confidence in managing panic symptoms:

Interoceptive Exposure: This involves deliberately inducing panic-like physical sensations in a controlled, safe environment. Examples include:

- Hyperventilation exercises to create dizziness and shortness of breath

- Spinning to induce dizziness

- Stair climbing to increase heart rate and breathing

In Vivo Exposure: Patients gradually confront real-world situations they’ve been avoiding due to fear of panic attacks. This might include:

- Crowded places (malls, theaters)

- Transportation (buses, airplanes)

- Exercise or physical activity

- Being alone or far from home

CBT Effectiveness

Research consistently demonstrates CBT’s effectiveness for panic disorder:

- Meta-analyses of 21 studies found CBT to be the most effective intervention for panic disorder.

- Brain imaging studies show that CBT reverses panic-related brain dysfunction, increasing activity in frontal and parietal regions.

- Response rates of 70-80% are commonly reported, with many patients experiencing complete remission of panic attacks.

Exposure Therapy

Exposure therapy, a specialized form of CBT, deserves particular attention due to its proven effectiveness for panic disorder. This approach is based on the principle that avoidance maintains and worsens fear, while systematic confrontation of feared situations leads to habituation and extinction of fear responses.

Types of Exposure

Graded Exposure: The therapist and patient collaboratively develop a fear hierarchy, ranking situations from least to most anxiety-provoking. Treatment begins with moderately difficult situations and gradually progresses to more challenging ones.

Flooding: This involves beginning exposure with the most difficult situations on the fear hierarchy. While potentially more efficient, flooding can be overwhelming and may lead to treatment dropout.

Systematic Desensitization: Combines exposure with relaxation techniques, helping patients associate feared situations with calmness rather than panic.

Mechanisms of Action

Exposure therapy works through several neurobiological and psychological mechanisms:

Habituation: Repeated exposure to feared sensations or situations leads to decreased physiological reactivity over time.

Extinction Learning: New safety associations are formed that compete with previous fear associations, essentially creating new neural pathways that inhibit panic responses.

Self-Efficacy: Successfully confronting feared situations builds confidence and mastery, reducing anticipatory anxiety and avoidance.

Emotional Processing: Exposure allows for cognitive restructuring of threat appraisals, helping patients develop more realistic beliefs about danger.

Pharmacological Treatments

While psychotherapy is often the preferred first-line treatment, medications play an important role in panic disorder management, particularly for individuals with severe symptoms or those who don’t respond adequately to therapy alone.

Antidepressants

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered first-line pharmacological treatment for panic disorder due to their effectiveness and favorable side effect profile:

Commonly Prescribed SSRIs:

- Sertraline (Zoloft): Well-tolerated with extensive research support

- Paroxetine (Paxil): FDA-approved specifically for panic disorder

- Fluoxetine (Prozac): Longer half-life, may help with discontinuation

- Citalopram and Escitalopram: Good efficacy with minimal drug interactions

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs), particularly venlafaxine (Effexor XR), also show strong effectiveness for panic disorder.

Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs), while effective, are generally reserved for treatment-resistant cases due to their side effect burden and potential cardiac risks.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines provide rapid relief of panic symptoms and are sometimes used in the initial treatment phase or for situational anxiety:

Commonly Used Benzodiazepines:

- Alprazolam (Xanax): Fast-acting, high patient satisfaction ratings

- Clonazepam (Klonopin): Longer duration of action, may require less frequent dosing

- Lorazepam (Ativan): Intermediate duration, good for acute symptoms

However, benzodiazepines carry significant risks including physical dependence, tolerance, and withdrawal difficulties, limiting their long-term use.

Treatment Response Rates

Pharmacological treatment effectiveness varies by medication class:

- Overall response rates: Approximately 80% of patients respond to appropriate pharmacological treatment

- SSRI/SNRI effectiveness: Response rates of 60-80% are typical

- Benzodiazepine effectiveness: High initial response rates but concerns about long-term dependence

Combination Treatment Approaches

Research suggests that combining psychotherapy with medication may be optimal for many patients, particularly those with severe symptoms or comorbid conditions. Combination approaches can:

- Provide rapid symptom relief (medication) while building long-term coping skills (therapy)

- Address different aspects of the disorder simultaneously

- Improve adherence to both treatments

- Reduce relapse risk compared to medication alone

Self-Help Strategies and Lifestyle Modifications

Acute Panic Attack Management

Individuals can learn several immediate coping strategies to manage panic attacks when they occur:

Breathing Techniques

Diaphragmatic breathing is one of the most effective immediate interventions:

- Breathe slowly through the nose for a count of 4

- Hold the breath for 1 second

- Exhale slowly through the mouth for a count of 4

- Focus on the sensation of air filling the chest and belly

Deep breathing helps counteract the hyperventilation that often accompanies panic attacks and activates the body’s relaxation response.

Grounding Techniques

Mindfulness and grounding help combat the derealization and depersonalization that often accompany panic attacks:

5-4-3-2-1 Technique:

- Identify 5 things you can see

- Identify 4 things you can touch

- Identify 3 things you can hear

- Identify 2 things you can smell

- Identify 1 thing you can taste

Focus Object Technique: Concentrating intensely on a single object and describing its details can help redirect attention away from panic symptoms.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation

Systematic muscle tension and relaxation can help reduce the physical symptoms of panic:medicalnewstoday+1

- Tense specific muscle groups for 5 seconds

- Say “relax” while releasing the tension

- Focus on the relaxation for 10 seconds

- Progress through all major muscle groups

Lifestyle Modifications

Several lifestyle changes can significantly reduce panic attack frequency and intensity:

Regular Exercise

Physical activity serves multiple functions in panic disorder management:

- Reduces baseline anxiety through endorphin release

- Improves stress tolerance and emotional regulation

- Provides controlled exposure to physical sensations similar to panic symptoms

- Enhances overall mood and self-efficacy

Recommended activities include walking, swimming, yoga, and tai chi. However, individuals new to exercise should start gradually to avoid triggering anxiety related to increased heart rate and breathing.

Sleep Hygiene

Quality sleep is crucial for managing panic disorder:

- Maintain consistent sleep and wake times

- Create a relaxing bedtime routine

- Limit caffeine and screens before bed

- Ensure the bedroom is cool, dark, and quiet

Dietary Considerations

Certain dietary modifications may help reduce panic symptoms:

- Limit caffeine intake, as caffeine can trigger panic attacks in sensitive individuals

- Moderate alcohol consumption, as alcohol withdrawal can precipitate panic

- Maintain stable blood sugar through regular, balanced meals

- Stay adequately hydrated

Stress Management

Comprehensive stress management is essential for long-term panic disorder management:

- Regular relaxation practice (meditation, yoga, deep breathing)

- Time management to reduce daily pressures

- Social support maintenance and development

- Problem-solving skills for handling life challenges

Prevention and Long-term Management

Relapse Prevention

Even after successful treatment, relapse prevention remains crucial since panic disorder can be a chronic condition requiring ongoing attention:

Maintenance Strategies

Continued Practice: Regular use of CBT skills, including:

- Ongoing exposure exercises

- Cognitive monitoring and restructuring

- Stress management techniques

Medication Maintenance: For individuals using psychiatric medications:

- Continue medications as prescribed even after symptom improvement

- Work with healthcare providers on any dosage adjustments

- Develop plans for gradual discontinuation when appropriate

Regular Monitoring: Periodic check-ins with mental health providers to:

- Assess symptom status

- Address emerging stressors

- Adjust treatment plans as needed

Identifying Warning Signs

Learning to recognize early warning signs of panic disorder recurrence:

- Increased anxiety sensitivity

- Avoidance of previously mastered situations

- Sleep disturbances or increased stress

- Physical symptoms without medical cause

Building Resilience

Long-term recovery involves building psychological resilience:

Emotional Regulation Skills: Developing healthy ways to manage difficult emotions through:

- Mindfulness practices

- Emotion identification and acceptance

- Healthy expression of feelings

Social Connection: Maintaining strong relationships and support systems that provide:

- Emotional support during difficult times

- Practical assistance when needed

- Opportunities for enjoyable activities

Meaning and Purpose: Engaging in activities that provide:

- Sense of accomplishment and mastery

- Connection to personal values

- Contribution to others or community

Conclusion

Panic attacks and panic disorder represent complex conditions involving intricate interactions between genetic vulnerability, neurobiological dysfunction, psychological factors, and environmental triggers. The hyperactivation of fear circuits in the brain, particularly involving the amygdala and its connected networks, creates the intense physical and psychological symptoms that characterize panic attacks.

Understanding these mechanisms has led to the development of highly effective treatments, with cognitive behavioral therapy standing out as the gold standard approach. The combination of cognitive restructuring and exposure-based interventions helps patients develop new, adaptive responses to panic-triggering situations and sensations. When combined with appropriate medications in severe cases, treatment success rates exceed 80%.

Prevention and long-term management require ongoing attention to stress management, lifestyle factors, and the maintenance of therapeutic gains. With appropriate treatment and support, individuals with panic disorder can achieve significant improvement in their symptoms and quality of life.

The future of panic disorder treatment lies in continued research into the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the condition, development of more targeted pharmacological interventions, and refinement of psychological approaches. As our understanding of the genetic and epigenetic factors continues to evolve, we may see more personalized treatment approaches that account for individual differences in vulnerability and treatment response.

For those experiencing panic attacks, it’s important to remember that these are highly treatable conditions with excellent prognosis when appropriate care is received. The combination of professional treatment, self-help strategies, and lifestyle modifications can provide substantial relief and help individuals regain control over their lives.