Childhood trauma represents one of the most devastating yet preventable public health challenges of our time. Far from being simply painful memories that fade with time, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) fundamentally alter brain development, create lasting changes in stress response systems, and establish pathways to addiction, mental illness, and chronic physical disease that can persist throughout an individual’s lifetime. Understanding these profound biological impacts is crucial for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies that can break the cycle of trauma’s intergenerational transmission.

Understanding Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) encompass a range of traumatic events occurring before age 18, including physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; physical and emotional neglect; and household dysfunction such as witnessing domestic violence, living with substance abuse, mental illness, or having an incarcerated family member. The landmark ACEs Study, conducted by Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control from 1995-1997, surveyed over 17,000 participants and revealed that ACEs are far more common than previously recognized.

The study’s findings were staggering: approximately 67% of participants reported at least one ACE, while 87% of those with one ACE experienced additional traumatic events. This research established that ACEs have a dose-response relationship with negative health outcomes—the more ACEs an individual experiences, the greater their risk for physical and mental health problems throughout life .

How Trauma Rewires the Developing Brain

The human brain undergoes rapid development during childhood, with crucial neural connections forming in response to environmental input. Trauma disrupts this normal developmental process, creating alterations in brain structure and function that can persist into adulthood. Think of optimal brain development like building a house with a solid foundation—trauma creates gaps in this foundation, leading to an unstable structure with holes in key areas.

Key Brain Regions Affected by Trauma

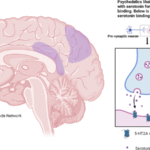

Childhood trauma particularly impacts brain areas involved in stress regulation, emotion processing, and executive function. The amygdala, which processes fear and emotional responses, becomes hyperactive due to ACEs, making individuals more sensitive to perceived threats and leading to heightened anxiety and fear responses. This hypervigilance represents an adaptive response to dangerous environments but becomes hyperactive when maintained long after the threat has passed.

The prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions like decision-making and impulse control, becomes less effective at regulating emotional responses after trauma. This impairment makes it harder for trauma survivors to make rational decisions, manage stress, and cope with life’s pressures. Changes to the hippocampus can impair memory and cognitive function while reducing the ability to properly assess and respond to stressful situations.

Research has identified that different types of trauma affect specific brain regions in distinct ways. For example, exposure to parental verbal abuse significantly targets the arcuate fasciculus, which connects speech processing areas, while witnessing domestic violence affects the inferior longitudinal fasciculus that connects visual and limbic systems. These findings suggest that the brain’s response to trauma is highly specific to the type of sensory input involved in the traumatic experience (NIH).

The Biological Embedding of Stress: HPA Axis Dysfunction

One of the most significant ways childhood trauma affects long-term health is through dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis—the body’s primary stress response system. The HPA axis controls cortisol production, and trauma exposure leads to sensitization of this system, creating lasting changes in how individuals respond to stress.

Dysregulated cortisol responses are detectable in adolescents with a history of child abuse and exposure to childhood violence. However, the specific pattern of HPA axis dysfunction varies by trauma type: exposure to non-intentional trauma is associated with normal daily cortisol patterns but elevated bedtime cortisol, physical abuse correlates with faster stress reactivity, and emotional abuse leads to delayed recovery following acute stress.

Adults with childhood trauma histories show a complex pattern of HPA axis dysfunction characterized by elevated baseline cortisol levels combined with blunted responses to new stressors. This suggests a hyperfunctioning stress system with little reserve remaining for robust responses to additional stress—essentially, the system becomes chronically activated and unable to mount appropriate responses when needed.

Epigenetic Mechanisms: How Trauma Changes Gene Expression

Beyond structural brain changes, childhood trauma creates lasting alterations in gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms—modifications that change how genes function without altering the DNA sequence itself. These epigenetic changes help explain how trauma becomes “biologically embedded” and can even be transmitted to future generations.

DNA methylation represents one of the most studied epigenetic mechanisms in trauma research. Studies have identified that childhood trauma is associated with altered methylation patterns in stress-related genes including BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), NR3C1 (glucocorticoid receptor), and genes involved in serotonin and dopamine systems. These methylation changes partially mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and depression, explaining approximately 20% of this association (NIH) .

Particularly concerning is evidence that childhood trauma can alter methylation patterns in human sperm, potentially inducing intergenerational effects that transmit trauma’s biological impact to children who never directly experienced abuse. This transgenerational transmission helps explain why trauma often runs in families and suggests that healing trauma may benefit not only the individual but also future generations.

The Inflammation Connection: Trauma’s Impact on Immune Function

Childhood trauma creates a pro-inflammatory state that persists into adulthood, with this immune dysfunction serving as a key pathway linking early adversity to later physical and mental health problems. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 25 studies involving over 20,000 individuals found that those exposed to childhood trauma had significantly elevated levels of inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

The inflammatory response to childhood trauma shows specificity by trauma type: sexual abuse is most strongly associated with elevated tumor necrosis factor-alpha, while physical abuse shows stronger associations with interleukin-6. These findings suggest that different types of trauma activate distinct inflammatory pathways, potentially explaining why various forms of childhood adversity lead to different patterns of adult health problems (NIH).

The inflammatory effects of childhood trauma appear to be mediated through epigenetic changes that affect glucocorticoid receptor function. Trauma leads to increased methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene, reducing the receptor’s ability to suppress inflammatory responses. This creates a vicious cycle where impaired cortisol function allows increased inflammation, which then further impairs glucocorticoid receptor function.

From Trauma to Addiction: Disrupted Reward Systems

The relationship between childhood trauma and addiction is both strong and biologically grounded. Individuals with a history of childhood trauma are five times more likely to develop substance abuse problems later in life, with this risk increasing in a dose-dependent manner with the number of ACEs experienced (ACA).

Trauma disrupts neural pathways involved in regulating stress, emotions, and decision-making, leading to dysregulation that impairs an individual’s ability to make healthy choices and contributing to the cycle of addiction. The alterations in dopamine and other neurotransmitter systems caused by childhood trauma create vulnerability to substances that can temporarily restore balance to these disrupted systems.

Research has identified that individuals who experienced multiple forms of childhood trauma are significantly more likely to engage in substance abuse, particularly cocaine, later in life. The ACEs study found dramatic dose-response relationships: compared to individuals with no ACEs, those with four or more adverse experiences showed a 700% increase in alcoholism, an 1100% increase in drug use, and a 3000% increase in attempted suicide.

The neurobiological changes caused by trauma—including alterations in stress response, emotional regulation, and reward processing—create a perfect storm for addiction vulnerability. Substances provide temporary relief from trauma-related symptoms like hypervigilance, emotional dysregulation, and chronic stress, but ultimately create additional problems while failing to address the underlying trauma.

Mental Health Consequences: The Trauma-Psychopathology Pipeline

Childhood trauma represents one of the strongest risk factors for virtually every category of mental illness. The dose-dependent relationship is particularly striking for depression, PTSD, borderline personality disorder, and substance abuse, with higher ACE scores predicting greater severity and treatment resistance.

The timing of trauma exposure appears crucial for determining specific mental health outcomes. Research suggests that trauma between ages 3-5 is associated with higher risk for developing PTSD, depression, and suicidality compared to exposure at other developmental stages. Similarly, sensitive periods exist for different brain regions: the hippocampus appears maximally vulnerable to sexual abuse between ages 3-5, while the amygdala shows peak sensitivity to maltreatment at ages 10-11 (NIH).

Trauma exposure in childhood is associated with a 50% higher risk of cardiovascular disease incidence compared to those with few or no stressful experiences. The psychological consequences include emotional dysregulation, behavioral problems, cognitive impairments, and difficulties forming healthy relationships—effects that create cascading problems throughout the lifespan.

Physical Health: The Body Keeps the Score

The physical health consequences of childhood trauma are extensive and severe, affecting virtually every organ system in the body. A systematic review analyzing over 250,000 subjects found that individuals with four or more ACEs had dramatically increased risks for multiple chronic diseases compared to those with no ACEs.

Cardiovascular Disease

Childhood trauma creates a particularly strong association with cardiovascular disease, with this relationship being even stronger in women. A case-control study found that patients with cardiovascular disease reported significantly higher numbers of early traumatic experiences, particularly emotional neglect, emotional abuse, and physical abuse. The association remained significant even after controlling for traditional cardiovascular risk factors, suggesting that trauma’s effects on heart health are independent of lifestyle factors.

The mechanisms linking childhood trauma to cardiovascular disease are complex and multifaceted. Trauma activates the sympathetic nervous system, triggering inflammation and immune system activation that can cause direct damage to coronary arteries and promote atherosclerosis. Additionally, trauma survivors often engage in health-damaging behaviors like smoking, excessive alcohol use, and overeating that further increase cardiovascular risk.

Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases

Childhood trauma significantly increases the risk of autoimmune diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, and chronic pain conditions. The chronic inflammatory state created by trauma contributes to conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and fibromyalgia. These associations highlight how early adversity can dysregulate immune function in ways that persist throughout life.

Metabolic Consequences

Trauma exposure is associated with increased rates of obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. The stress-induced alterations in cortisol and other hormones can promote weight gain, insulin resistance, and metabolic dysfunction. Additionally, trauma-related changes in eating behaviors and physical activity patterns contribute to metabolic health problems.

The Intergenerational Cycle of Trauma

Perhaps most concerning is evidence that childhood trauma’s effects extend beyond the individual to impact future generations. Specific outcomes such as violence, mental illness, and substance abuse—all correlated with multiple ACEs—can represent ACEs for the next generation through exposure to parental domestic violence, mental illness, and substance abuse.

This intergenerational transmission occurs through multiple pathways: genetic vulnerability, epigenetic modifications, parenting behaviors, and environmental factors. Children of trauma survivors are more likely to experience ACEs themselves, creating cycles of adversity that can persist across generations. Breaking these cycles requires interventions that address not only individual trauma but also family systems and community factors.

Resilience and Recovery: The Power of Neuroplasticity

Despite the profound impacts of childhood trauma, there is significant hope for healing and recovery. The same neuroplasticity that makes the developing brain vulnerable to trauma also provides the foundation for recovery and resilience throughout life.

Neuroplasticity-informed interventions have shown significant effectiveness in promoting trauma recovery. A meta-analysis found that interventions such as mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and neurofeedback were associated with significant improvements in PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms. These approaches work by promoting positive changes in brain function and structure, essentially rewiring the neural networks affected by trauma.

Key principles for supporting neuroplasticity in trauma recovery include personalization of interventions, use of evidence-based neuroplasticity-promoting techniques, trauma-informed care approaches, and collaborative treatment relationships. Specific strategies that promote neuroplasticity include mindfulness-based interventions, cognitive-behavioral therapy, neurofeedback training, and physical activity.

Trauma-Informed Care: A New Paradigm

The recognition of trauma’s pervasive impacts has led to the development of trauma-informed care—a framework that recognizes the widespread impact of trauma and integrates knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices. Trauma-informed care emphasizes safety, trustworthiness, peer support, collaboration, empowerment, and attention to cultural, historical, and gender issues.

This approach transforms traditional treatment models by recognizing that many symptoms and behaviors previously seen as pathological may actually represent adaptive responses to trauma. Rather than asking “What’s wrong with you?” trauma-informed care asks “What happened to you?”—a shift that reduces stigma and promotes healing.

Prevention and Early Intervention

Given the profound and lasting impacts of childhood trauma, prevention represents the most cost-effective and humane approach to addressing this public health crisis. Primary prevention involves creating safe, stable, and nurturing environments for all children, while secondary prevention focuses on early identification and intervention for at-risk families.

Early intervention strategies that show promise include parent education programs, home visiting services, mental health support for families, and community-based programs that strengthen social support networks. These approaches work by addressing risk factors for trauma while building protective factors that promote resilience.

School-based programs that teach emotional regulation skills, provide safe environments, and identify at-risk children also show significant promise for preventing trauma and its consequences. Creating trauma-informed schools helps identify children who have experienced ACEs and provides appropriate support before problems become entrenched.

Treatment Innovations and Future Directions

Emerging treatment approaches are increasingly sophisticated in addressing the complex neurobiological impacts of childhood trauma. Technology-based interventions including virtual reality, brain-computer interfaces, and mobile applications are expanding access to evidence-based treatments.

Pharmacological approaches that target the inflammatory and stress system dysfunction caused by trauma are showing promise. Anti-inflammatory medications and glucocorticoid receptor modulators may help address the biological embedding of trauma, particularly when combined with psychotherapeutic interventions.

Precision medicine approaches that use genetic and epigenetic markers to personalize treatment selection are emerging as potential game-changers in trauma treatment. Understanding individual differences in trauma susceptibility and treatment response could lead to more effective, targeted interventions.

Conclusion: Healing the Hidden Wounds

Childhood trauma represents a profound public health crisis that affects brain development, stress response systems, immune function, and virtually every aspect of physical and mental health. The dose-response relationship between ACEs and negative health outcomes demonstrates that trauma’s effects are not inevitable—they are preventable and treatable.

The good news is that our understanding of trauma’s biological impacts is leading to increasingly effective interventions. Neuroplasticity research shows that the brain retains the capacity for healing and growth throughout life, providing hope for trauma survivors regardless of when they seek help.

Moving forward, addressing childhood trauma requires a multi-level approach that includes primary prevention to stop trauma before it occurs, early intervention to minimize damage when trauma does happen, and sophisticated treatment approaches that address trauma’s complex biological and psychological impacts. By understanding how childhood trauma becomes biologically embedded, we can develop more effective strategies to promote healing and break the intergenerational cycles of adversity that too often characterize human experience.

The science is clear: childhood trauma is not just a psychological issue—it’s a medical condition that affects every system in the body. With this understanding comes the responsibility to act, creating safer environments for children and more effective treatments for those who have already been harmed. The hidden wounds of childhood trauma may be deep, but they are not beyond healing.

Sources

- Childhood Trauma and the Immune System: A Complex Interaction That Can Lead to Biopsychosocial Pathogenesis

- The intersection of childhood trauma and addiction

- Childhood trauma and adulthood inflammation: a meta-analysis of peripheral C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α

- How Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Affect Brain Development

- Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study

- Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Consequences on Neurobiological, Psychosocial, and Somatic Conditions Across the Lifespan

- The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis