Our brains are amazingly busy—even when we’re doing “nothing.” When we’re daydreaming, recalling memories, or imagining the future, a set of brain regions called the default mode network (DMN) springs to life. Scientists have found that when this network gets out of balance, it can fuel a range of mental health challenges: depression, anxiety, PTSD, schizophrenia, autism, and ADHD. Understanding how the DMN works—and sometimes misfires—gives us fresh clues about why these conditions arise and how we might treat them better.

What Is the Default Mode Network?

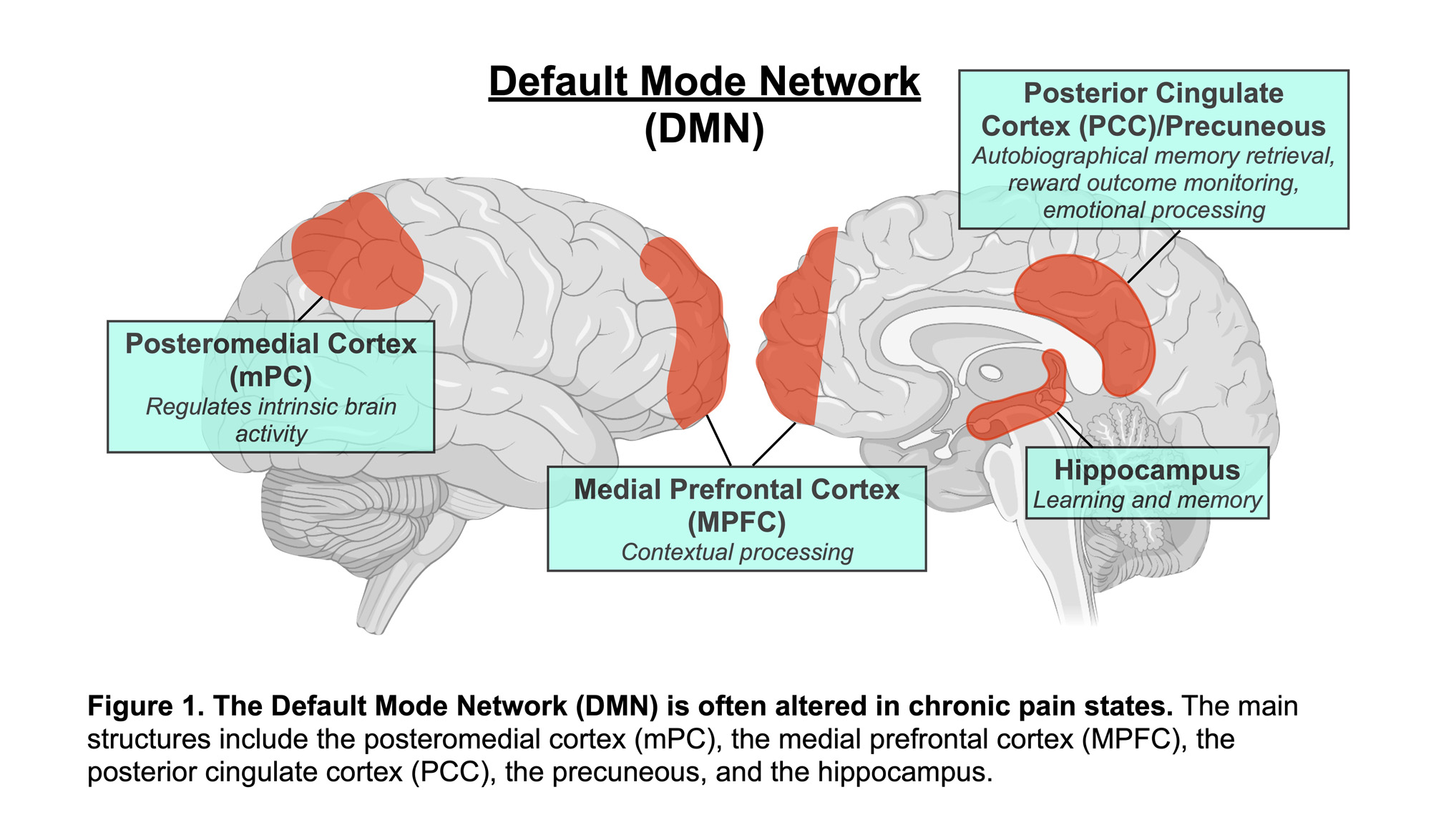

Imagine your mind drifting through memories, self-reflection, and thoughts about other people. That “inside” mental activity is powered by the DMN, which includes key hubs like:

- The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (thinking about yourself)

- The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and precuneus (recalling memories)

- The angular gyrus (connecting ideas)

When you switch to a focused task—solving a math problem or reading—these regions quiet down, making way for task-positive networks that handle attention and action. A healthy brain toggles smoothly between these modes. But when that toggle gets stuck, trouble can follow.

How the DMN and Task Networks Should Dance

- Resting / Mind-wandering: DMN ON, task networks OFF

- Focused Task: DMN OFF, task networks ON

When this balance falters, your mind might get “stuck” on internal thoughts at the wrong times—leading to anxiety or inattention—or fail to process personal experiences effectively.

Depression: Rumination on Repeat

People with depression often replay negative thoughts and memories. Research shows their anterior DMN (the front part) stays overly connected, reinforcing self-critical thinking and rumination. Meanwhile, the communication between front and back DMN areas can break down, making it hard to integrate memories in a healthy way. The result? A relentless loop of negative self-talk and social withdrawal.

Anxiety: Worry and the Unwired Mind

Anxiety disorders involve constant worry—often about the future. Studies suggest anxious brains struggle to turn off the DMN when they need to concentrate. Instead of focusing on the present, people with anxiety remain locked in internal worry loops, making it hard to switch attention outward.

PTSD: Memories That Won’t Let Go

In PTSD, traumatic memories keep popping up uninvited. Researchers have found that the DMN in PTSD shows unique connectivity patterns: it may disconnect in some areas but over-connect in others, keeping the “memory replay” system in overdrive. Effective therapies, like prolonged exposure, actually help restore balance to these networks—correlating network normalization with symptom relief.

Schizophrenia: When Self and Reality Blur

Schizophrenia can distort one’s sense of self and the line between internal thoughts and reality. While overall DMN changes vary, stronger connections between mPFC and PCC have been linked to better social function in schizophrenia—hinting that targeted DMN interventions might improve rehabilitation outcomes.

Autism and ADHD: Challenges with Reflection and Focus

- Autism: People on the autism spectrum often show weaker DMN connectivity, particularly between mPFC and PCC. This may underlie difficulties in imagining other people’s thoughts and reflecting on their own mental states.

- ADHD: In ADHD, the DMN sometimes fails to switch off during tasks. That lingering DMN activity can pull attention inward at the wrong moments, leading to distractions and impulsivity.

Why DMN Disruptions Happen

Several factors can throw the DMN off balance:

- Intrusive Self-Focus: Overactive DMN circuits fuel rumination and worry.

- Task Interference: Poor DMN deactivation interrupts concentration.

- Memory Fragmentation: Disrupted posterior DMN leads to fragmented or intrusive memories.

- Network Imbalance: Disturbed coordination between DMN and task networks destabilizes mood and control.

- Early Life Stress: Childhood trauma can reshape DMN development, increasing vulnerability to later disorders.

Turning DMN Insights Into Treatments

Better Diagnoses

Researchers are exploring resting-state DMN scans as potential biomarkers to detect conditions early, distinguish similar disorders (like PTSD vs. depression), and predict who will respond best to therapy.

Brain Stimulation and Training

- TMS (Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation) can target DMN hubs to help regulate mood and reduce rumination.

- Neurofeedback teaches people to consciously modulate their own DMN activity.

- Cognitive training and mindfulness practices strengthen the brain’s ability to switch networks effectively.

Personalized Care

By mapping each person’s unique DMN patterns, clinicians may tailor treatments—combining medication, neuromodulation, and specific psychotherapies—to rebalance the network most effectively.

A More Balanced Brain, A Healthier Mind

The DMN is essential for our inner lives—our memories, self-awareness, and imagination. But when its rhythms go awry, mental health can suffer. Modern neuroscience is showing us that mental disorders often reflect network-level disruptions rather than flaws in single brain regions. As we learn more about the DMN’s role, we’re finding innovative ways to restore balance—helping people move from cycles of rumination and suffering into healthier, more adaptive ways of thinking and feeling.

Sources:

- What is the Default Mode Network’s Link to Mental Health?

- Default Mode Functional Connectivity is Associated with Social Functioning in Schizophrenia

- Findings of PTSD-specific deficits in default mode network strength following a mild experimental stressor

- Instability of default mode network connectivity in major depression: a two-sample confirmation study

- Default Mode Network Connectivity and Social Dysfunction in Major Depressive Disorder

- Default mode network dissociation in depressive and anxiety states

- Default-mode brain dysfunction in mental disorders: a systematic review